Convocational Development

It takes a village to make an app.

Large software platforms like Twitter, Facebook and YouTube are more than just code and data: to a human being they feel like worlds. The way worlds are created and governed determines the kind of worlds they can be. Using worlds created for value-extraction for democratic purposes is not impossible, but it is difficult. If you want a world that makes democratic and open behaviour easy, you need to create it in a democratic and open way. But how do you do that?

Here I put forward my solution: making a creation world that sits beneath the main one. The creation world is host to a community that makes the design decisions for your larger software world. The community uses open source protocols, and puts energy into explaining the code in layman’s terms so that it is possible for an ordinary user to understand how the code currently works and articulate what exactly they would like to change about it.

This creation world itself also needs to be modifiable so that the best environment for new visitors and constructive discussion can be iterated towards.

Worlds and their problems

Facebook, Twitter, Youtube and Reddit are not just software services. They are combinations of large amounts of code, data, users, rules, customs, guides, moderators and even robotic entities. They are too big for a person to understand or model. Even the people who work there can’t understand them on their own — these collections of software services, users and the experiences they create are worlds. I say “are” rather than “act as” or “are experienced as”, because they are able to cause real consequences in the lives of the people who use them.

But these worlds aren’t free of problems.

- Facebook spreads lies and sells information to propagandists.

- Twitter is full of noise, pointless arguments and incredible hostility.

- YouTube promotes conspiracies and combative authoritarianism.

- Arbitrary decision-making is a common complaint about all these platforms.

Why is it so difficult to use Twitter and Facebook for progressive purposes?

When people try to use Twitter and Facebook for social change, they go about it in a few ways that generally suffer because of the design of the sites. They might type how they would like the world to change, which people can read, or share amongst the people who already agree with it. They might start a group to work together on activities, and then find the group is dysfunctional because of the way the information is displayed and presented to people.

Twitter is designed to make you feel as if you’re part of an ever escalating conversation. Facebook is designed to make you feel as if you’re having a fun time with your friends. Neither of those feelings are the same as making quality social change. These worlds act as a friction on whatever you want to do, because they aren’t designed for that activity.

Design, once you get past inspiration and are working on a project, is about choosing the trade-offs that you are willing to make. Twitter and Facebook are designed to get you to use Twitter and Facebook more. The trade-offs their development teams make are in the service of that goal, which means the assumptions that are embedded in the worlds are often counterproductive to positive social change. The following examines one of those assumptions in closer detail.

One embedded assumption on Twitter is “a tweeter wants as many people as possible to see one of their tweets”. So, all tweets, unless they come from a locked account, can potentially be seen by anyone, and a tweet that was shared with you can be shared by you. A single message can move around a local network, then jump to an adjacent local network and then jump to another one and on and on. There is no limit internal to Twitter on how far a tweet can travel. Which means there is no limit on how far out of context a message can be taken.

Personally I have watched this particular assumption cause a lot of problems in progressive communities, the main one being that people who actually have very little material disagreement in their viewpoints end up vehemently opposed to one another because they misread each other’s tweets. The usual situation is that they don’t see a caveat that was posted earlier and take a single tweet to be the totality of what the tweeter means. They argue against it, the original tweeter has no way to see that their attacker didn’t see a caveat, and so has to assume that the disagreement is malicious.

Compounding this, viewers of the conversation have no idea what the participants are responding to because they may only follow one half of the conversation, so they are confused and often jump in and try to clarify the situation for themselves only to make it noisier for everyone else. This ends up creating an affect that I call “What the fuck is everyone talking about?” that is not conducive to being a part of an effective organisation.

Why do they have these problems? Prefiguration and Conway’s Law

The anarchist concept of prefiguration is a powerful one: broadly it states that the way you organise politically determines the kind of outcomes that you can get. This is the basis of their critique of the Soviet Union, if you use a top-down authoritarian political organisation strategy i.e. the Leninist party, you end up with a top-down authoritation state i.e. the USSR.

In computer science there is a similar rule, called Conway’s Law, that “organisations which design systems … are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organisations.” Basically, the way you create a world limits the kinds of world you can make.

Now, it could be said that the problem with these companies isn’t their methodology, but their profit driven goals. However my point is that their methods flow directly from their profit driven goals: the “Agile” methodology (which I describe in detail later) is a natural consequence of a venture capitalist ownership structure.

Put simply, the problems Twitter and Facebook have originate from their optimisation for engagement. They optimise for a number because it’s the logical way to run an organisation when they have to show progress while not actually returning any money to their investors. Something to bear in mind is that their investors are not strictly trying to make a profit either. They’re trying to increase the price of the shares of the company when they eventually sell it on. And the way to do that is to keep costs down while building a product that can be seen as valuable without having to put much energy into valuing it.

So, the pressure of having to continually make progress while spending as little money as possible created the methods of world creation that Twitter and Facebook use today. But what are those methods?

A History of Deliberation Processes

To understand how our current software worlds were made, we need to understand how past ones were.

Every software project has a deliberation process, a way that determines where effort should be spent, whether that’s coding new features, investigating new frameworks, debugging methods, optimising experiences etc.

Deliberation processes have evolved over time, as technology has. When software was made by one person, or a small group of people, that deliberation process was as simple as the developers asking themselves “what do I want to work on next?”. I call this Naive Development, because it is the method that isn’t a method, it’s just whatever ends up happening (but this is still a process). Naive development can be exhilarating, but if it’s one person, is likely to be slow, and if a group, be uncoordinated and chaotic. It can also be highly ego-driven because people identify strongly with the parts of the software they create, leading to irrational decisions and co-operation breaking down. If you want software to be made in a predictable way, you need a development methodology i.e. a creation process that collaborators understand how to use.

I’ve defined the various development methodologies by asking where the design decisions for the piece of software come from.

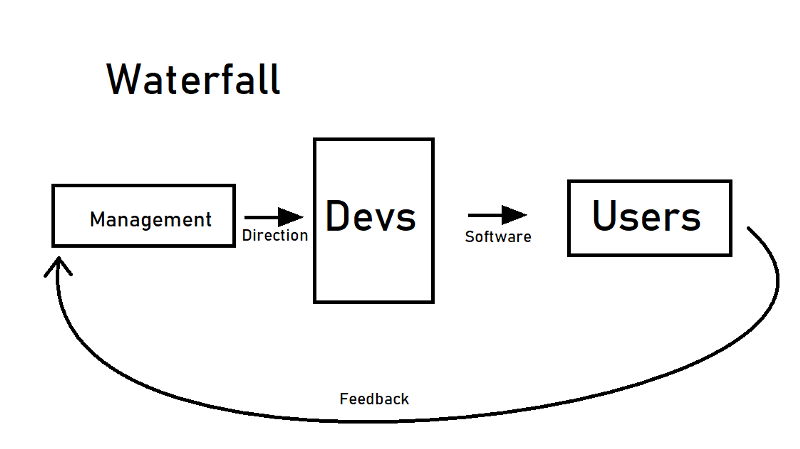

- If they come from managers, then it’s Waterfall.

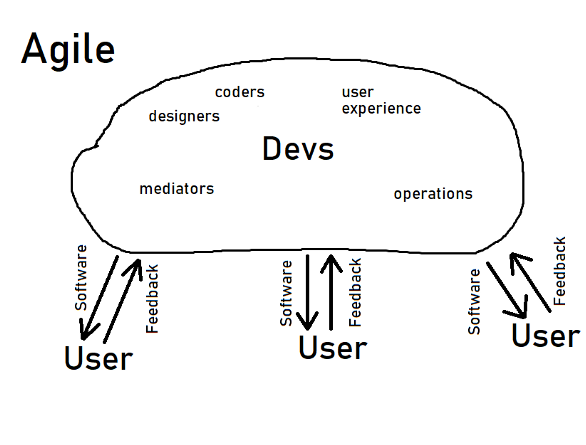

- If they come from developers observing users it’s Agile.

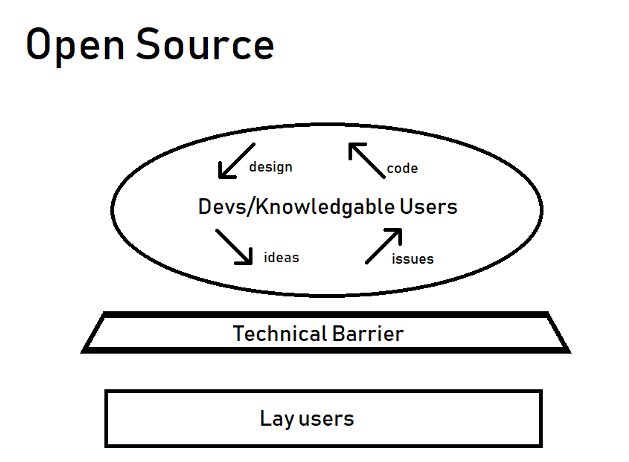

- If they come from devs who are also users it’s Traditional Open Source.

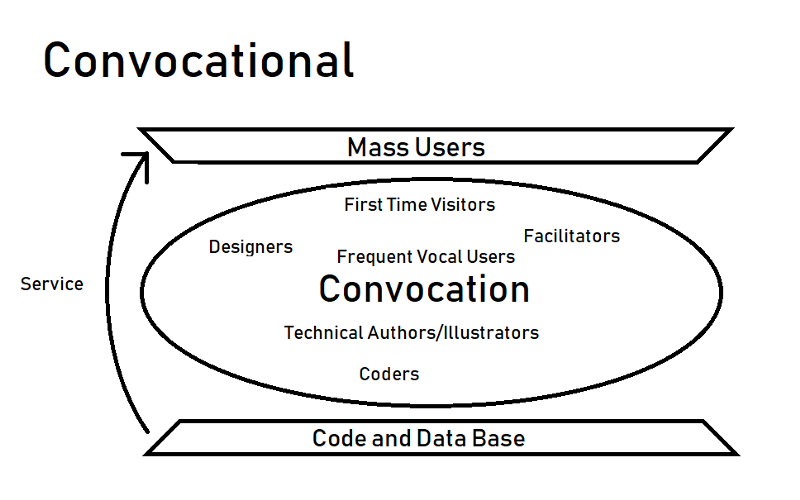

- And if it’s devs, non-technical users and various kinds of mediators communicating together, it’s Convocational.

These are ideal types. All organisations that create software are unique in some way. If you go to an Agile meetup you can hear about all kinds of companies experiencing unique situations, but they’re advised to approach these situations in the same way: give your developers a target and the right level of freedom to hit that target.

What is Waterfall?

Waterfall, or as it used to be called “Software Development” (it was given the name waterfall when the agile movement started in the 90s and they needed a name for the process they weren’t using) was the answer to Naive development. Managers decide what features are going to be added next, then designers and developers make them, the software is tested, then released to the users. Users then feedback to managers who decide what to work on next.

Waterfall is an improvement on having one person making software and trying to make the decisions themselves, because it allows larger projects to get done quicker by adding multiple developers and splitting up tasks for them to work on. It also adds a process for a developer to bring up ideas that they’ve had because they can tell a manager about it who can decide for them (usually by consulting other developers).

But when feedback from users has to filter through managers, it slows down and is seen through the prism of management. Management also doesn’t solve the ego problem, it just moves it up a level, so software can still be developed based on what person is fixated on. Agile aims to solve these problems.

Agile at its core is based around constant iteration based on user feedback. It uses metrics to determine what users are doing, and also do qualitative user experience research, like asking users to come in and use a product while talking about it in front of the developer. An example of a common practise is A/B testing, where different users of a website are chosen to see slightly different versions of that site e.g. on one day half the users who use facebook see an ad after every three posts and half of them see an ad after every four posts, and then whichever set has more ad clicks is the version that moves forward.

Agile is a corporate method of creating software, so it’s focused on value, finding features that can produce new customers at the lowest cost to the organisation. Usability has to be a priority for an agile development organisation, because customers aren’t willing to put much time into learning how to use their software. They’re usually in competition with other products, so the products are easy to use, but very similar to things that have already been proven to work in the marketplace (and they aren’t interested in things that aren’t profitable).

Most of our current software worlds use some variation of an agile methodology. Their worlds tend to have a small group of semi-benevolent creators that add changes to the platform, then measure the users on how they react to those changes in order to extract the most value from them for advertisers. These are extractive worlds. Their aim is to have you use them more often so that they can sell more ads based on your information.

Twitter, Facebook and YouTube are optimised for “engagement” which is any kind of user-interaction with the world, weighted by how much energy they require on the part of the user. So every like, comment, view or click counts as an engagement. Every design choice is designed to increase that number, because it’s very easy to measure, and is a good proxy for how many ads can be sold to the world. But engagement means any kind of engagement, good or bad. The platforms are created so that if you post funny stuff, they’ll get you to post funnier things. If you post cute videos, they want cuter ones. If you type angry, hateful speech, they reward angrier, more hateful things. (This is where the Logan Paul fiasco came from, at each step he needed to become more and more outrageous in order to maintain and grow his audience).

Traditional Open Source

Agile and open source are not totally separate, because Agile companies often release projects under open source licenses. But here I’m talking about open source as an ideal, where the developers and the users are the same people.

Traditional open source projects usually have a tight community of members who all have at least a moderate amount of technical knowledge, because that knowledge is required for a person to be involved in either coding, or commenting on the code. So, open source tools tend to be limited in scope to those needed by computer programmers, network admins, the kinds of people with the skill to write them. Because the user base and creators are so close, the products generally have a lot of useful features that are difficult to learn how to use. The developer’s incentives are only to make the software more useful for the person using it, because the developers are the users.

Benefits of open source:

- Vettable, for security purposes, secrecy is not the best practise. If malicious and benevolent security experts are both in the dark about a service, only the malicious expert has the motivation to research the architecture. But benevolent security experts outnumber malicious ones, if given the opportunity they can look at the service and diagnose any vulnerabilities before they become serious.

- Forkable, if your world starts getting bad results, and you aren’t willing to change it, people can simply pick the things they like about your world, and develop it in a different direction.

- The issue with traditional open source is that the projects are limited by high barriers to entry, because it requires knowledge of the technologies that the software uses, which in turn limits the functionality that is imagined or requested, because of the kinds of lives that technically skilled people live (i.e. fiscally healthy, secure, stable, comfortable, generally more cerebral than emotional).

Finding people to contribute to open source can also be an issue, if all the people working on it already have some level of coding skill, they want to spend their time on the project coding, not telling people about the project, or guiding new users to be competent enough to help. The projects can find it hard to get resources other than developer time, and people who have other skills beyond coding, don’t get utilised because they don’t see a way they could be useful, because there’s not an opening for them in the deliberation process.

What is the next step?

To get open source programs with mass appeal requires the removal of those technical barriers to entry. This means there needs to be a space for deliberate and patient explanations of what the source code actually does, and why it has been done that way.

This space would be a creation world, that sits beneath the larger, “real” one. This creation world is called the Convocation (the name comes from the complex patterns that starlings make when they fly together). A similar architecture to a creation world, is the way a massive online game like World of Warcraft has a forum to discuss upcoming changes and the impact that has on the user base. The difference is that rarely do the WoW forums actually instigate the changes, they mostly just comment on them and players provide tips to each other on how to approach them. But the idea of a “real” world where actions happen and a supplementary world where they are discussed is what I’m proposing.

The fundamental difference between the convocation and traditional open source is that energy is put into facilitating discussions between users, coders, graphic designers etc. Documentation and instructions are often the weakest part of an open source project, and that excludes people who don’t have the time or ability to assemble a mental model of the open source software and its capabilities from just the code and the meagre promotional materials. The convocation starts as a basic web forum, but evolves tools and cultures that enable greater participation in the development process itself. Better accessibility, better security, better understanding of the perspectives of both developers and users.

Convocational development is open source, but it’s also open design. The features are inspired by individual users, but more importantly by the users in concert with each other, and the developers.

What is it like to visit a convocation?

With a convocational approach, it should be possible for a user of an application to become a developer of said application as they move closer and closer to the code base. I call the following scenario the user-developer ladder.

If we imagine the surface level of the application as that of the normal mass user, most users will never leave this layer of the world. But one of our users might have an idea. They leave the application-world, and go into the convocation.

The convocation is set up to be very friendly to first-time users, guiding them to where they can raise their issue and idea. This is because they are important barometers on the health of the application as they have no interest in making the convocation seem like it’s working: all they care about is the app. So they need to be able to be heard loudly and clearly, but also the convocation can’t spend its time answering the same questions all the time.

So, they post their idea or issue, and then other users of the convocation can read and respond, ideally in an encouraging and inclusive way. If the user returns to the convocation to stay on their issue, they will be discussing it with other users, and developers.

If they stick with the discussion, they can be involved in thinking of a change to the software. If they want, they can be part of the team that finalises the change, and documents it. And if they’ve done research, they could actually be the person to commit the change to the codebase.

This journey takes them from a user to a developer of the app. From layperson to priest to a god!

How do you start a convocation?

Briefly:

Construct the app’s modification system.

Make sure the modification system can make decisions about the modification system.

Construct the app.

Find a communication platform (i.e. a service that hosts online conversations). So this could be a web forum, or a github page, maybe even a very long google doc! Basically you’re choosing the software that hosts your interactions. Different platforms will be better suited to different things, but ideally the one you choose will have some degree of customisation available and be friendly to first time usage.

Start filling with people who can comment on your application. Ideally a good mixture of people with differing levels of expertise and skill levels. Make a prototype of your application.

Possible concrete applications of the convocation: pair coders with authors who work together on written explanations of updates or proposals. Have users talk about common problems with each other, and allow developers to explain why these issues arise, what trade-offs are being made.

Is anyone already doing something like this?

MMORPG’s are pretty much required to have forums, especially in beta testing, to let users ask each other questions and to consult about any changes. This is because they are paid by the users and so have to optimise for their pleasure.

Glitch is a website for coders to try out fun things and share code with each other. It has a forum for discussing its platform.

Wikipedia does a similar thing with its articles and talk pages. There is a “normal” world, and then a subworld that comments on it. They are close to a convocation but they don’t build the application that way, and their voting system is not transparent to new users.

The Mozilla Foundation that develops firefox is open to new users to come and talk about features that they’d like. I don’t know if they go as full on the user-developer ladder as they could.

The blockchain people are having difficulty at the moment with what they call “the governance problem”, which is really just their lack of a well thought through convocation once the development team and user environment gets above a few dozen people. Telegram (an encrypted chat room service) is not enough.

If you want to make vast software worlds that people fall in love with, you need to communicate with your users and allow them to communicate with each other.

What tensions could arise from convocations?

Convocations will have tensions: issues that can never be resolved, but must be continually addressed to ensure the convocation continues to be fruitful. Think of these tensions like the tensions of ropes that hold up a tent. Without the tension the tent would fall down. Too much tension, the ropes snap and the tent collapses.

-

There are going to be people suggesting things that aren’t taken forward, are they continually being ignored, do they feel that the discussions are always dominated by some individuals or groups? Do they think that deliberations are too obscure, wastes of time, go too slow, too fast? The way to address this is trust, and socialisation, to realise that we are all human beings. But there’s no formula for trust, it just has to be attended to.

-

The tension between the convocation and the foundational users. 80% of the talk in the convocation will be by 20% of users. But 80% of the visitors to the convocation will be visiting for the first time. The first time experience has to be delightful, they need to be heard, they need to not have to learn very much, and be able to use the convocation very easily. First time users are important signals for the health of the app, because they have no stake in the health of the convocation, they have beginner’s mind. Their impression isn’t coloured by a desire to see the convocation as working, they just want to get done talking about whatever they thought of about the app.

-

The changes to the app need to be legible to the majority of users. The convocation has to be frequently grounded to explain why any change is necessary, and to see if it is desirable. There are clear general goals that everyone shares, but if specific goals aren’t aligned that is useless.

-

The convocation’s visibility to itself. How do people know where to go for different things? Is it obvious where a discussion of a problem or new feature should go? As more things are discussed, previous sortings will become diluted. The scope never gets thinner.

-

As the convocation grows, complicated theories and understandings become simplified as new users seek to learn and deploy them as fast as possible. How is the inevitable degradation of the culture over time addressed? Is it a lossy or lossless compression? Are ideas displaced or integrated into the fabric of the convocation?

-

The level of paranoia about security. An app designed to challenge an economic system will have the power of that economic system levelled against it. But to fear and suspect everyone is clearly not a desirable situation. So how do you find the right balance between convenience for the user and security for the system? This can only be addressed through discussion between the more security minded and convenience minded members of the convocation.

Now what?

I am using Convocational development to make my workplace organising application. At the moment, I am putting together a prototype to comment on and researching platforms in order to begin inviting people to join the community.

The next step of exploring Convocational development is to start giving names to the things that occur within and around a discussion platform for an application. To do this there needs to actually be both an application and a discussion platform. If you’d like to be involved, please email me with the subject line “Convocation Help”.

I encourage people who are making software to think about their feedback process and whether a formal convocation is worth setting up.