An Introduction to Wobbly

Wobbly is a workplace organising platform being designed and prototyped by a small voluntary team of developers. It’s a communication and coordination tool with structures and processes modelled on the IWW’s organising style (hence the name, coming from the IWW nickname). We’re creating a space for energetic, powerful, and democratic unions to win struggles and grow.

The Problem

The gig economy has brought a host of new challenges for workers with it. Low wages, lack of insurance or sick pay, and precarious working conditions are just some of the problems that food couriers, freelancers, and Uber drivers face. Improving working conditions is only attainable with the pressure of collective power. And the way to build that power is through traditional organising, enhanced with a powerful set of digital tools.

Those tools, at the moment, don’t exist. Organisers are forced to use a combination of email, WhatsApp conversations, or Facebook groups, which are hard to use for organising at scale. Using the corporatist tools is like trying to write a novel with a crayon. It’s technically possible to do it, but no reasonable person would do so if they had the choice of something better.

It’s pretty easy to infiltrate a WhatsApp conversation, as some Deliveroo organisers have found. It’s difficult to manage once they get above ~100 members, and co-ordinating between different groups across multiple localites is not a feature the WhatsApp developers have considered at all. This is what Wobbly aims to address.

The vision for Wobbly

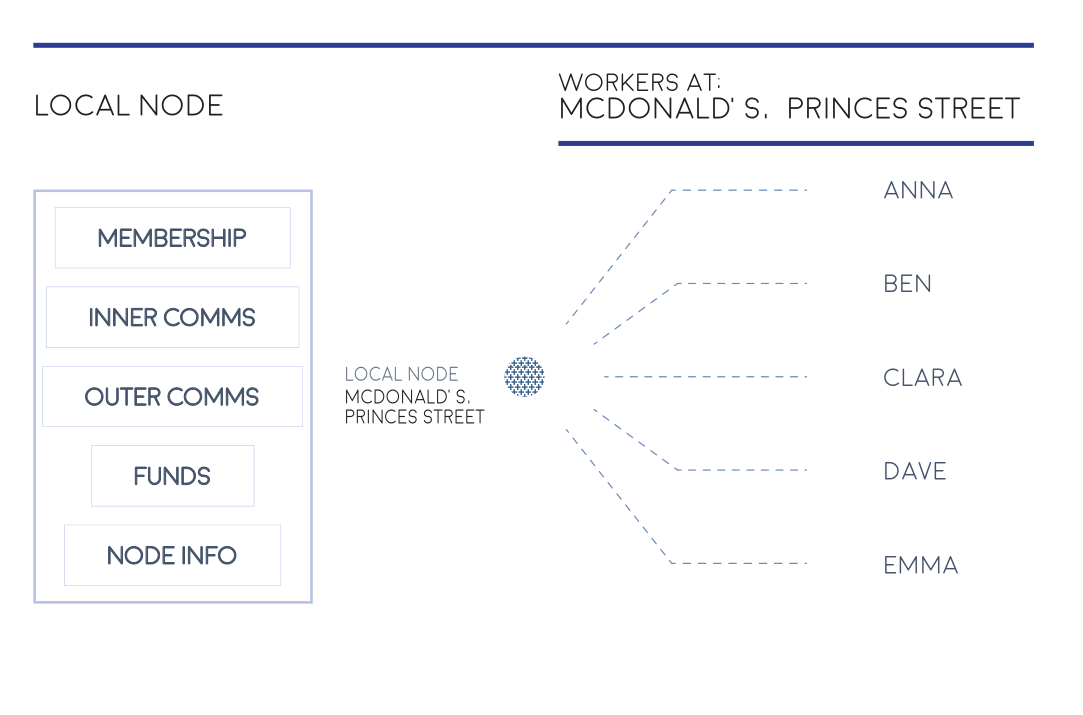

Wobbly differs from other chat applications by building federated organisation in from the start. Every user enters the app by joining or creating a local node – what might be called a branch in traditional organising. They do this by searching for their workplace when they open the app for the first time. The nodes are named after their workplace, and can be geotagged to make them easier to find.

The local node is the base unit of the system, used to represent workers who regularly meet face-to-face (or have the potential to be able to). An example would be all the workers at the McDonald’s on Princes Street in Edinburgh. The size of the node is such that the current members should be able to independently verify that a prospective member is who they say they are, and should be a member of the node. Basically, in a local node the members should know each other (or be able to know each other) without the app.

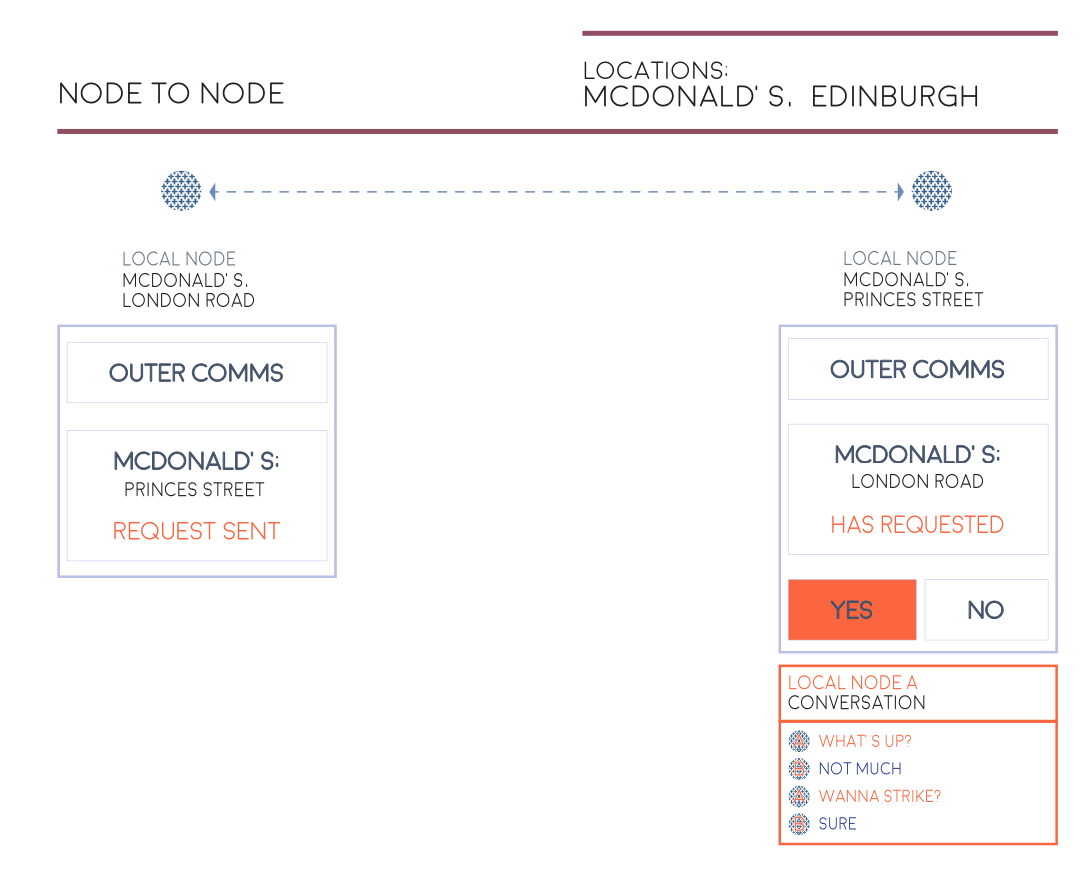

In each node there are three parts: First, encrypted communication that allows workers to talk to each other. Second, a way to put forward proposals and vote on them. Third, and this is the part that no one else is working on, a way to communicate with other nodes: Group-to-Group Communication.

If workers at McDonald’s Princes Street want to talk to workers at McDonald’s London Road, the Princes Street McDonald’s node sends a communication request, the McDonald’s London Road node accepts, and then they have an open channel.

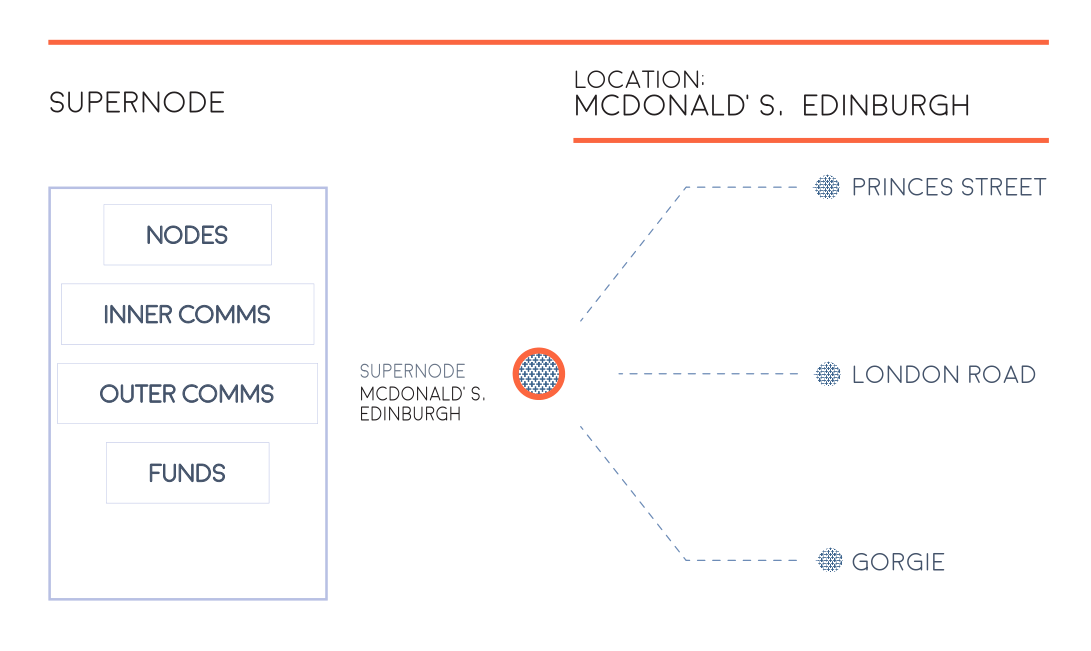

If workers in nodes want to do things like make shared resolutions, strike together, or organise shared events, they can form a supernode. To take the previous example, the McDonald’s Princes Street node and the McDonald’s London Road node create a proposal to form a supernode called McDonald’s Edinburgh. The members of the local node vote on the proposal, and if it’s successful, a new supernode is created that the other branches of McDonald’s within Edinburgh can also join. Then, using mandated recallable delegates (or some other democratic system) to communicate, the supernode can coordinate the local nodes that constitute it, and direct the shared resources towards their chosen ends.

Our plan is that multiple supernodes will be able to come together to make supernodes of their own - an ultranode. The relationship of a supernode to an ultranode is the same as the relationship between a local node and its supernode. It uses the same democratic system that links the local nodes and supernodes, this time with the supernodes selecting delegates to put forward mandates for the ultranode.

So, to continue our example, McDonald’s Edinburgh and McDonald’s Glasgow could form an ultranode called McDonald’s Scotland. Because the democratic systems are ultimately derived from the local nodes, like McDonald’s Princes Street and McDonald’s London Road, the ultranode remains controlled by the workers themselves, minimising their reliance on a hierarchical union leadership to take struggles forward.